Experiencing the experienced at

Art Basel Miami Beach

Never having a reason to go, I’d long consigned Art Basel Miami as a place for friends and frenemies, but not for me. But this year, out of the great blue nothing, I got my chance.

My boyfriend and I were lucky to go to Basel on a VIP day, making it luxuriously sparse and hushed, a pristine time for art encounters. We glided around, mingled with the Mexico City contingent, and later I nibbled on a gummy, causing me to intermittently giggle and stand stupid, drooling in front of a big nice art, supremely spaced out and loving every minute.

The first booth we wandered into was Esther Schipper, near the entry. Grabbing me was Simon Fujiwara’s Who’s the Little Who in the Bigger Splash? (2021), a collage of colored poster board depicting a poolside bear, innocently a little drunk on himself, stagger-prancing off a lowdive.

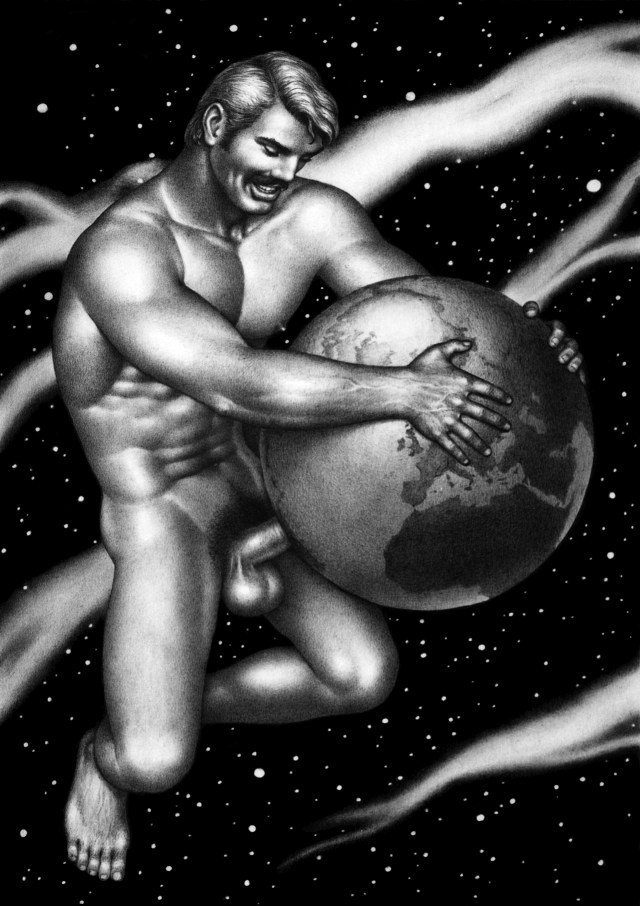

There is something immediately a little gay in this scene of gleeful narcissism, of making the world your cumrag, an urge reminiscent of the unnamed 1976 Tom of Finland stud pumping planet earth as if a Fleshlight. But in the Fujiwara, we get the specter of narcissism’s conjoined twin, voyeurism, in the distant director’s chair, linked by a question repeated to the figure’s crotch, both symbols of the widely seen and the popularly unseen, forever teased and the pre-eminently whored out.

The honey-drunkard is an anthropomorphic Vinn overlap, embodying what the question mark has in common with heart, which also pops up on a phone screen. The interplay invites interesting connections about how creator and audience—vanity and emotional metrics, love and likes—collide in the euphorically naive. What has traditionally been an ego stroke tied to an age or era of self discovery has mutated today into an omnichannel impulse, thanks to attention algorithms, to stay suspended in it—and, as the title suggests, win. A life in service to our avatars— our “little who”—making the biggest splash.

A ways down, at Anton Kern, freezing at Alessandro Pessoli’s confrontational mixed-media work was just the natural thing to do. In The God of Forgiveness (2021), the viewer is held at gunpoint by a they/them donning a mildly flamboyant getup, flanked by two loyal doggies and crudely backdropped by what could be large flames, a town on fire. Cartoony outlined flatness interrupts hazy airbrushing and gestural marks, making for a near-palimpsest effect in the face—another example of collaging painting styles that (as I’ve said before) feels made for our recombinant, pastiche-laden and nihilistically flattened moment. (This sensibility is playing out in fashion too, Gucci being one example: It’s not so much what you wear anymore, but what you wear it with; beauty today resonating when it lies in tension, instead of merely with itself.)

What’s also interesting—unnerving—is the uncertainty as to the figure’s left hand, in a situation where deciphering body language is of life-or-death importance: Are they gesticulating? Beckoning you closer? Have they just tossed you a bouquet of flowers, fragrant wad of grace, a hail Mary? Is this a potentially lethal trick? Or a test? Can we trust this happy-go-lucky sojourner, or are we dealing with an angel in disguise, made grotesque by a deranged proposition? Forgiveness can be hard to read.

Sikkema Jenkins had lovely cutout felt works by Arturo Herrera, a TU grad—go ‘Canes—that conveyed the connotative timeless wisdom, technical mastery and disciplined beauty associated with Asian calligraphic characters and bamboo brush painting tradition without the actual (i.e., limiting) characters, representations and meanings per se.

After a muted coffee break of spacing out while gazing at the smiling flight-attendant prosecco ladies at their stations, we set out for new territory.

At Sadie Coles, near one of Sarah Lucas’ tube ladies, a lump of body lies with itself in an untitled work from 1985 by Alan Turner, renowned surrealist and remixer of body-ody-oddities. Here, our tendency to self-smother lies sexy and shirtless in the grass, faces turned soup, but more likely face soup. Whether we feel like the voyeur or one of the akimbo halves, we begin to wonder what would happen if we got to third base with our inner selves. The intrinsic deformity of the human condition, of co-existing with our our jumbled facets, becomes an uncomfortable, if comical cuddling act, romantic even, that Turner serves ambivalently as a here-nor-there (everywhere!) fact of life.

Lots of artmaking is like driving: a sequence of slight veers and sensible, reactive adjustments in steering, even when there’s no destination in mind. But there is some art that evinces a process closer to getting in a wreck, crawling out of your flaming car, deciding you didn’t need to appear in court anyway, then walking off for lunch. It’s work—and logic—gone sideways, turning what was perhaps peculiarly interesting into something spectacular.

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Smartphone - regazze con borsa e zaino (girl with bag and backpack) (2018) exemplifies a trajectory suddenly shifted, having suffered a drastic change in psychological funding, causing corners to be cut, a final image to be finagled, jury-rigged. It’s art that has itself lived through something, survived it, and bears the marks of that experience. In this way, it is a testament unto itself, and its integrity, having nakedly endured an existential struggle.

Art that genuinely does this merits the further consideration from the viewer. How has the smartphone, opaquely referenced in the title, filtered this woman and her ostensible baggage? How is it changing perception? Are we looking through the screen? Do we too, as digitally perceived entities, faintly spray from a unique set of cultural nodes and values scattered across a cartesian grid of sociocultural signifiers, increasingly becoming oozing QR codes to be scanned, discovered, and variously zeroed in on, depending on the perceiver’s own sacred blot? Maybe we are fools for thinking the title has anything to do with what’s shown; maybe finding a link to the names we make for ourselves online is just as contrived.

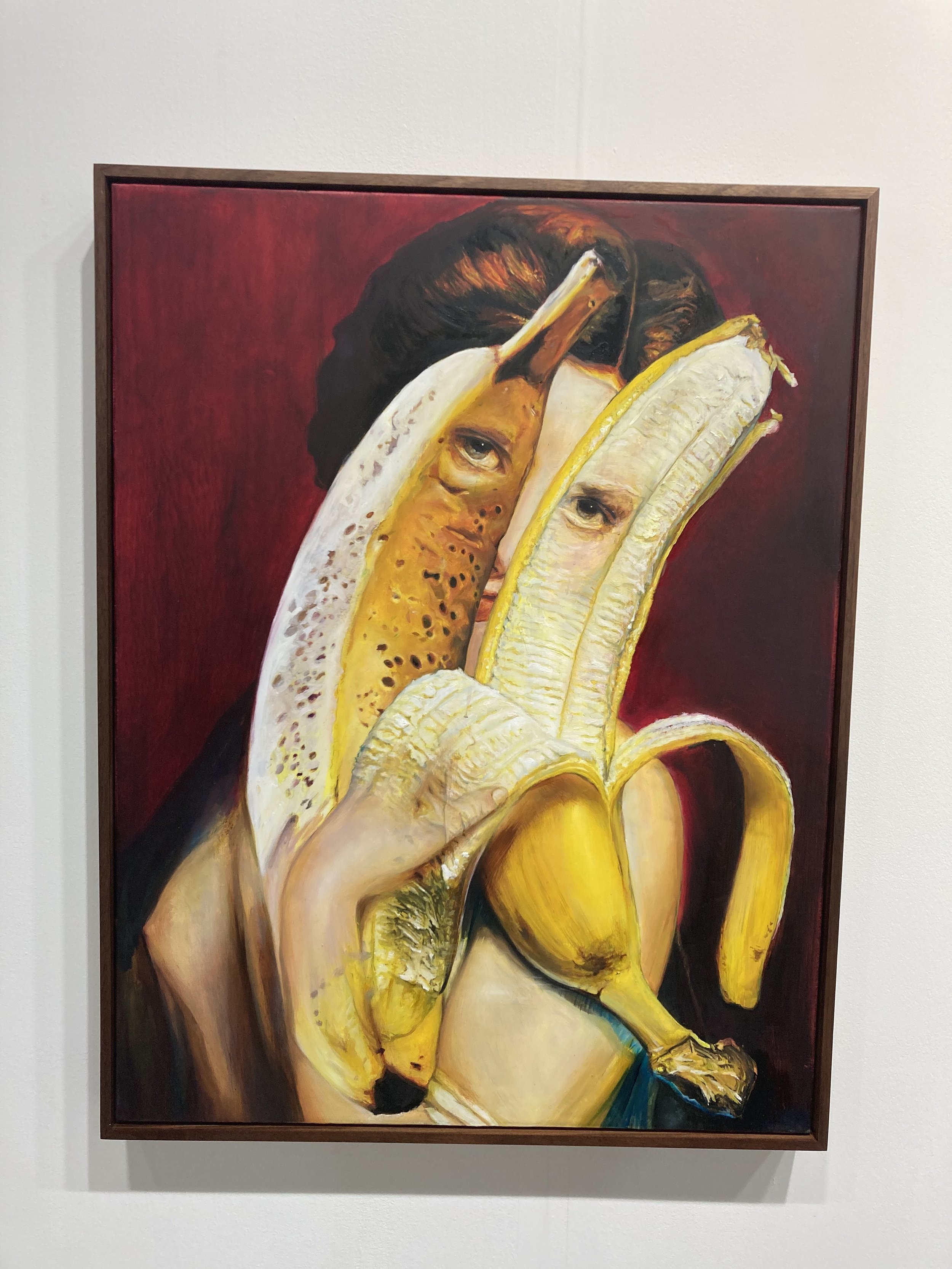

Another was this piece by Thomas Lerooy, at Randolphe Janssen, whose captive Gatsby-esque gaze lends fresh notions to chiaroscuro, its rot; the idea of shadow as unpeeled light. That light is preserved in darkness, goodness in seeming bad, and so on.

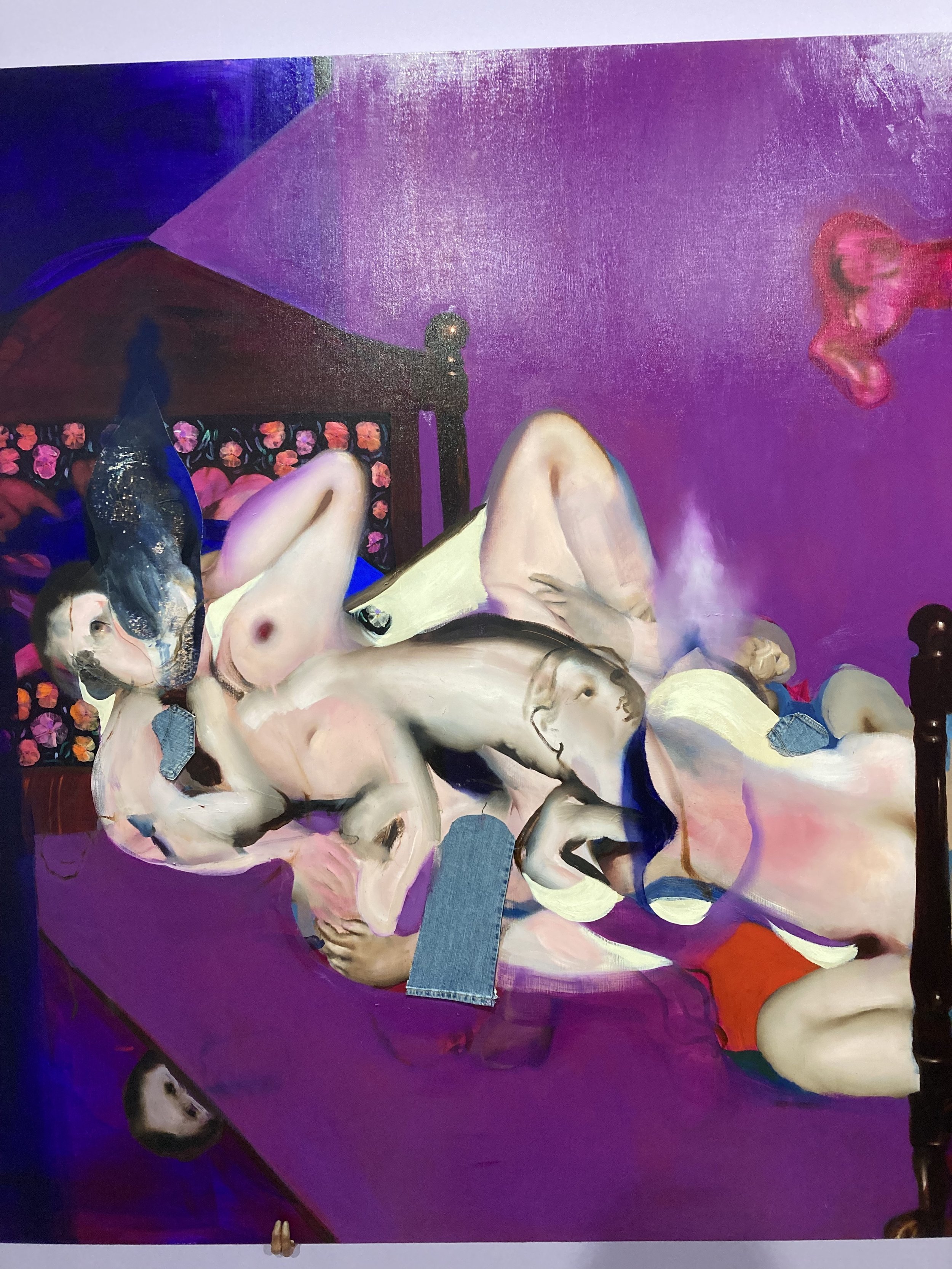

Centered in the lilac-hued booth of Company Gallery, a wooden bed frame was echoed by a similar bed painted on a canvas on the wall behind it, this time with a mattress and tangle of nude-ish figures — all the work of Ambera Wellman, whose characteristic forms borrow and share smeared mounds of flesh and shadow, a trick of commotion blurrily reminiscent of kinetic art. What results is nondescript nasties, and here, in the confusion and bewilderment, the chance to observe human copulation with alien eyes — perhaps those of a possible child, who peeks from under the frame. A marvelous meditation on removal, depiction and the craftiness of folklore, of strewn humanistic traditions.

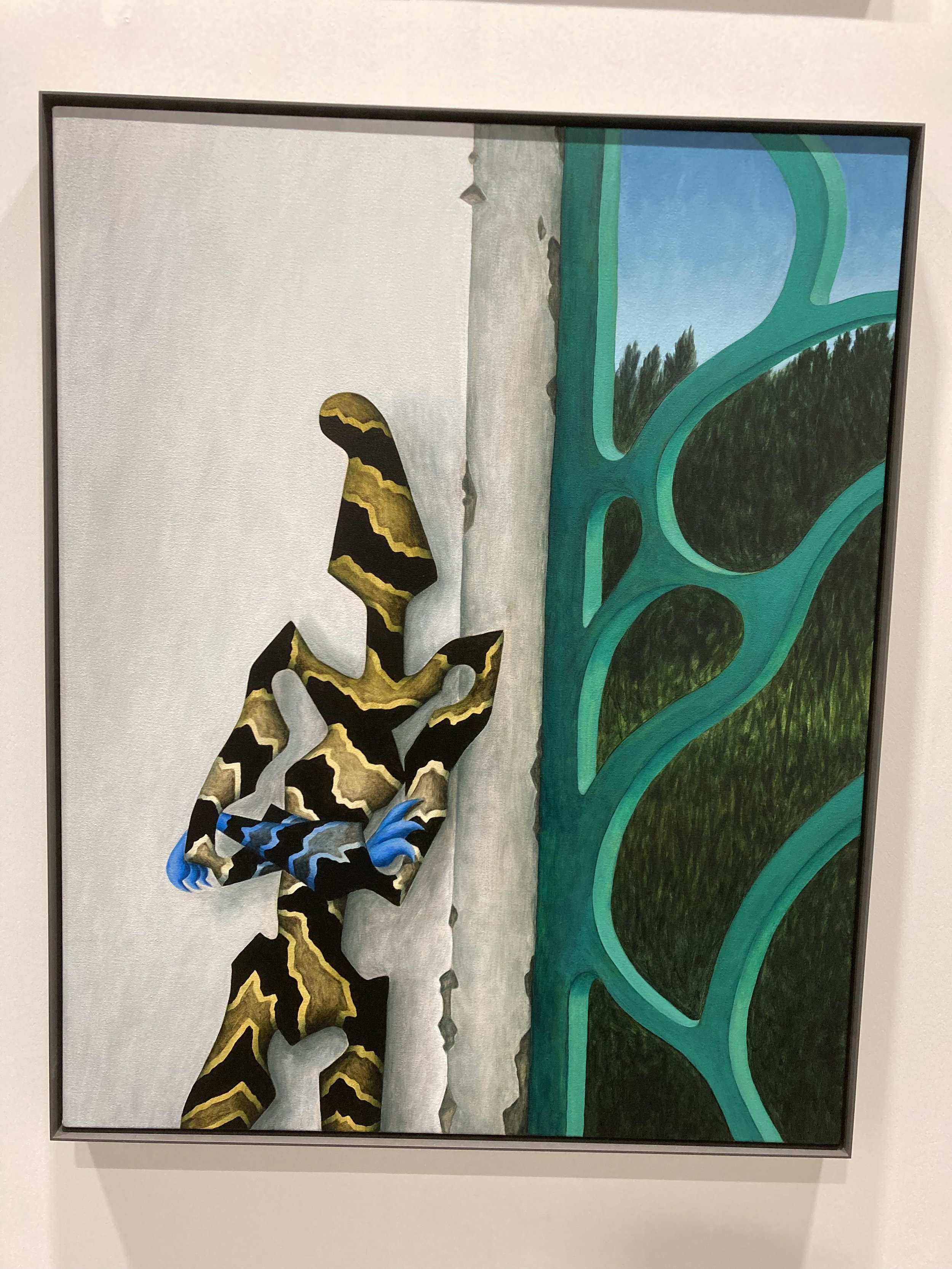

The repeated stripe figures central in the work of Chilean artist Alejandro Cardenas, at Almine Rech, suggest an alternate reality, but exhibit the same ol’ human behavior and tropes, causing a cold reflection on what kind of creatures we are. How? By divorcing the pesky intangibles of situation and behavior from the familiar (and distracting!) visual context that so often makes us take things for granted.

With impressionistic, intimate scenes of queer contemplation and mirth, Salman Toor throws light on the forgotten beauty of quiet flamboyance.

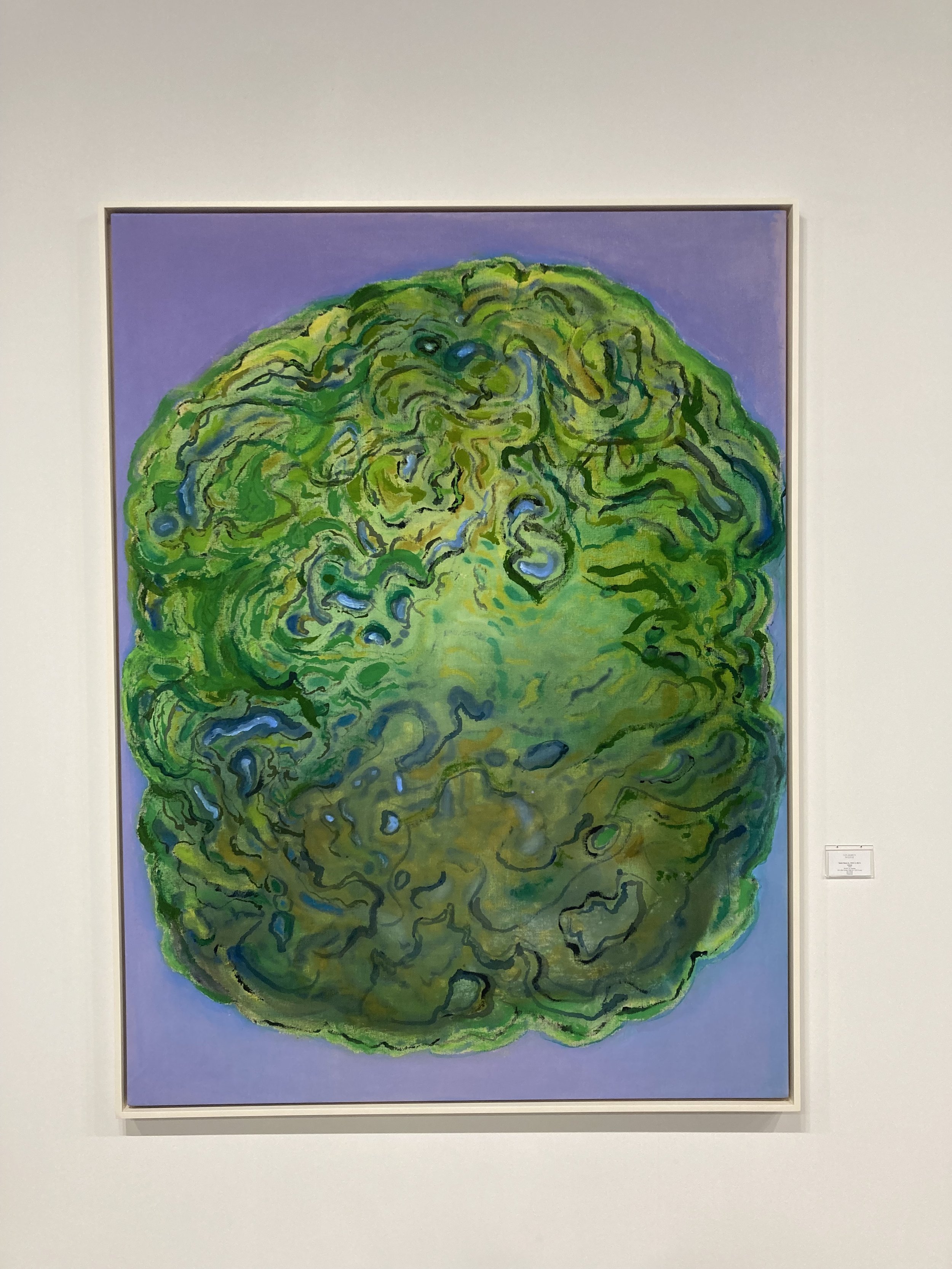

By effecting a gradual, gradient-slow realization that this piece of produce has turned, Lettuce brings a hard-wired evolutionary instinct into focus.

Alex Da Corte’s piece, mounted on house siding, is easily a shrine fixed to impermanence, or a well-placed advertisement from the arachnid industry aimed at insects — yet another preyed-upon species of consumerist suckers.

Elizabeth Glaessner’s piece (left) was among many to feature figures submerged in water—a shared motif amid life in lockdown and a never-ending onslaught of disconcerting news.

These impressively realistic sculptures by Chloe Wise, which adorned a less interesting painting, get at the absurdity of our silly little combos of consumption that, in the end, no matter how familiar or foreign, no matter how cute, are just varying degrees of psychically charged garbage resold with nostalgia.